Are we suppressing one of Mother Nature's oldest and most effective bug-fighting mechanisms by force-feeding patients when they have lost their appetite during an infection?

A Phd student in physiological sciences from Stellenbosch University, Gustav van Niekerk, argues this might be the case and is calling for a reassessment of this standard medical practice.

In an article published in the high-impact journal Autophagy this week (6 April 2016), Van Niekerk and researchers from the Department of Physiological Sciences at SU argue that appetite loss during infection or sickness has a very important function. And that is to enhance the ability of cells to perform autophagy, a process which literally means "eating of self".

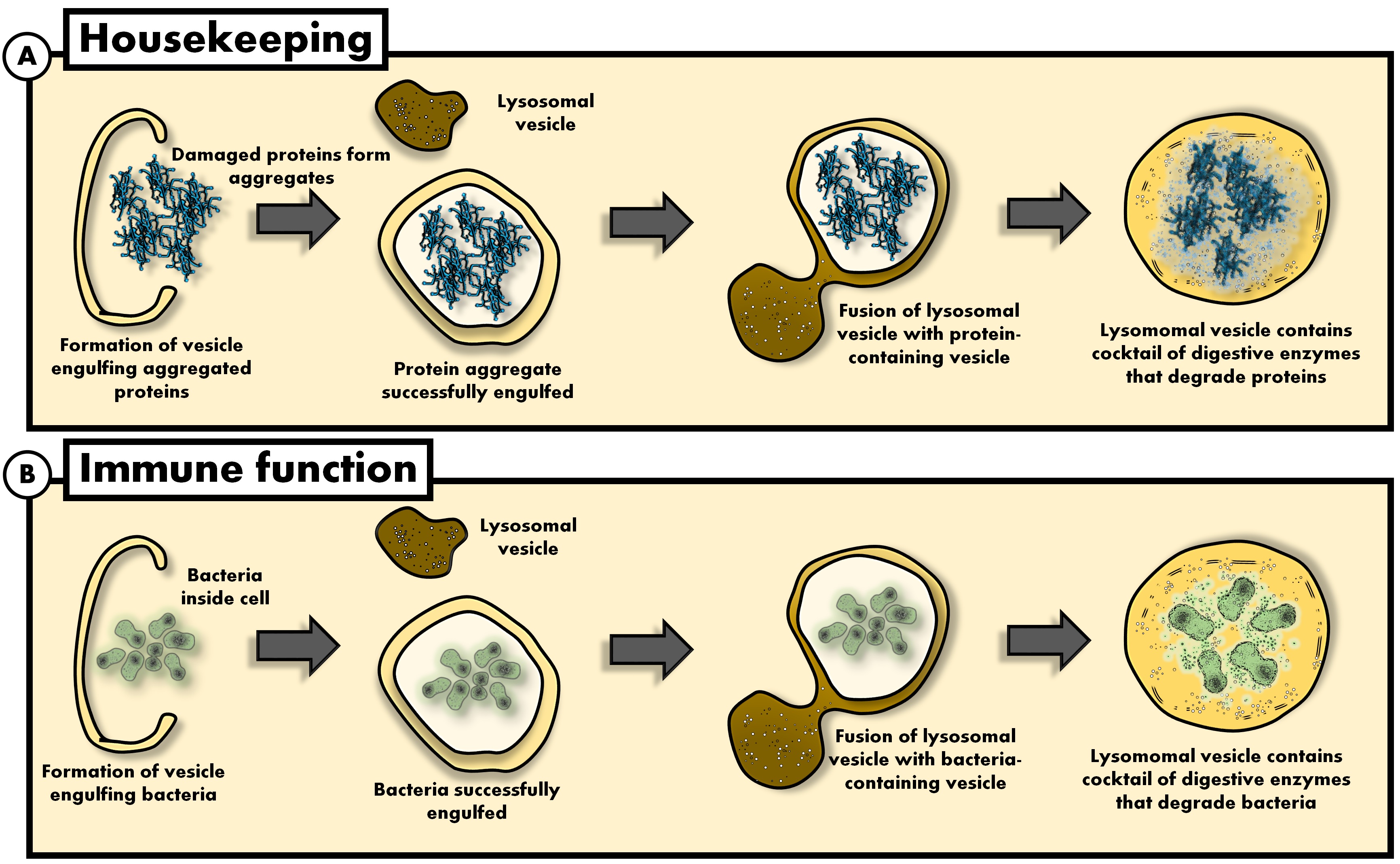

Under normal circumstances the cells in your body use autophagy (a kind of cellular 'recycling process plant') to clear the garbage generated by the wear and tear of the parts in a cell. Through autophagy, the cell is able to recycle the debris or junk that could otherwise have caused damage to the cell.

The degraded material is then used as fuel to generate new parts. In other words, all the cells in your body are continuously being regenerated in order to function optimally.

Van Niekerk and co-authors argue that short-term fasting during an infection can be beneficial, since cells which are deprived of nutrients are forced to upregulate the recycling process (autophagy). In turn, bacteria and viruses invading the cell can be degraded by the very same recycling process (see Figure 1).

Van Niekerk explains: "The immune system is often seen as the 'army', while 'normal' cells such as liver cells and neurons are seen as 'civilians'. In this view, invading bacteria or viruses harm the 'unarmed civilian' while the 'military' (the immune system) are dedicated to fight off an infection."

However, 'normal' cells are not quite as defenceless.

"We argue that an upregulated autophagy acts as a cell's self-defence mechanism and that it plays a critical role in the body's immune system.

"In this way, 'civilian' cells are in fact acting like 'partisan forces' halting the spread of the infection while the 'professional forces' (immune cells) are mobilised."

Prof. Anna-Mart Engelbrecht, head of the Department of Physiological Sciences and one of the co-authors, says this new way of understanding the role of autophagy has important implications for the medical field: "It has also been shown that cancer patients who fasted before chemotherapy experienced less harmful side effects usually induced by chemotherapy such as fatigue, weakness, headaches, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea."

Firstly, the researchers argue for a re-evaluation of nutritional support in the context of controlled underfeeding, where enhanced autophagy may provide superior support.

Upregulating autophagy may also have additional benefits. Chunks of bacteria and viruses processed by the cell's recycling plant can also be passed on to immune cells. In turn, the immune cells can be 'trained' to recognise the bacteria and viruses and form antibodies against them. This would suggest that upregulating of the recycling plant (autophagy) may be an effective way to enhance vaccine efficacy.

The researchers stress, however, that shorter-term nutritional withdrawal should not be confused with the well-established immune-inhibiting effect of long-term starvation. They also point out that there are a number of circumstances in which nutritional supplementation may provide a therapeutic benefit. As an example, some pathogens are able to 'hi-jack' certain steps in the autophagic proses. Therefore, evaluating patients according to pathogen-type may indicate infections in which permissive underfeeding as opposed to aggressive supplementation may prove more effective.

The co-authors on the article are Prof. Anna-Mart Engelbrecht, Dr. Ben Loos and Dr Theo Nell. The work was supported by the Cancer Association of South Africa (CANSA), the National Research Foundation (NRF) and the Medical Research Council (MRC).

Figure 1. The cellular process of autophagy play a critical 'housekeeping' function (A) but is also utilised for immune function (B). In this example (A), the cell 'targets' a protein by painting it with a kind of molecule which designates the protein for degradation, followed by the formation of a membrane that 'engulfs' the protein. As a result, the protein becomes 'isolated' from the rest of the cell. Then, other vesicles which contain a cocktail of digestive enzymes fuse with the protein-containing vesicle. As a result, the protein gets "chopped-up" into amino acids which can then again be used by the cell. The same 'autophagic machinery' used to digest cellular components are also used to degrade bacteria (B). Graphic: Gustav van Niekerk

Contact details

Prof. Anna-Mart Engelbrecht

T: 021 808-4573

E: ame@sun.ac.za

Mr. Gustav van Niekerk

M: 076 801 7048

E: 14088576@sun.ac.za

Issued by Wiida Fourie, media: Faculty of Science, Stellenbosch University, science@sun.ac.za, 021 8082684, 071099 5721