Since most flowers consist of both male and female parts, they can potentially mate with themselves (self-pollination) or a different plant (outcrossing).

But does this process only happen by chance?

While plants are often viewed as relatively passive participants in their own mating process, simply waiting for the birds and the bees to distribute their pollen for them, researchers from Stellenbosch University believe they have found (more) evidence of female choice in plants.

In a research article published in the journal Current Biology recently, Prof Bruce Anderson and Dr Corneille Minnaar describe this phenomenon after they used different colored quantum dots to track pollen movement between Wachendorfia paniculata flowers and their pollinators.

W. paniculata, commonly known as the butterfly lily, is endemic to the Western Cape. It belongs to a small group of plants that exhibit the phenomenon of handedness or enantiostyly – left-handed flowers have female parts (stigma) deflected to the left, but stigmas are deflected to the right in the flowers of right-handed plants. In the case of W. paniculata, two out of three anthers (male parts) are deflected to the opposite side of the stigma, while the third anther is on the same side.

Botanists have been perplexed by handedness since the 1800s. In his last scientific correspondence, just days before his death on 19 April 1882, Charles Darwin wrote to a fellow botanist for seeds of another handed plant, namely Solanum rostratum, so that he could “have the pleasure of seeing the flowers and experimenting on them".

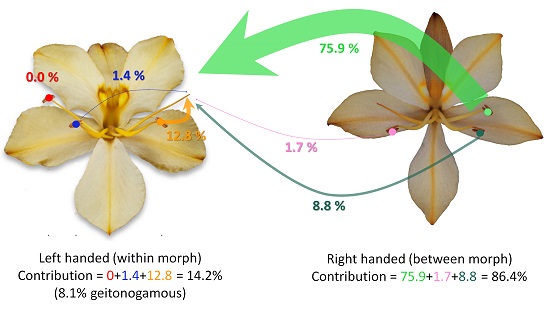

It has since been established that handedness is a strategy used by flowers to prevent mating with oneself which can lead to pollen loss and inbreeding: Left-handed flowers place most of their pollen on the left side of a pollinator, where they are picked up by right-handed flowers, while right-handed flowers do exactly the opposite. This strategy increases the efficiency of pollen movement between plants, reducing self-pollination, and promoting genetic diversity and healthy offspring.

But Prof Anderson and Dr Minnaar noticed that while the lower anthers (male parts) of W. paniculata placed pollen primarily on the flanks of carpenter bees, upper anthers placed more pollen on the wings. This led to pollen quality hotspots on their wings where pollen receipt would almost certainly result in outcrossing. In contrast, the probability of receiving selfed pollen was higher if pollen was picked up from the flanks of the bees.

“Think about how planes come in for a landing at an airport – it is all very structured and planned with guiding lights and flags all the way," explain Prof Anderson. “Flowers are structured in the same way. Using nectar and guiding marks, flowers lure pollinators into consistently landing in the same spot so that the pollinators can have easy access to the flower's nectar but at the same time efficiently pick up and deposit pollen."

Because bees land quite consistently on W. paniculata flowers, the female parts or stigmas were able to position themselves in such a way that they made more frequent contact with the wings of carpenter bees, where most of the high-quality, outcrossed pollen would be found.

Prof Anderson says the exploitation of these outcross-pollen hotspots on carpenter bee wings explains why W. paniculata has much higher rates of outcrossing than expected by the enantiostyly condition.

“If sexual selection is considered to be selection for traits that increase mating success, then this could be thought of as a form of female choice by plants. Our finding, that the stigma of W. paniculata uses pollen position as a rough surrogate for quality, implies that a form of mate selection can take place prior to, or during mating," they write in the article.

While Darwin realised that female choice drove the evolution of showy traits such as peacock tails in animals, he did not consider it as a possibility in plants.

“As the anniversary of Darwin's death on 19 April 1882 has just passed, we wonder what he would have thought if his wish had come true and he had managed to study handedness in plants," Prof Anderson concludes.

Click here to listen to a podcast with Prof Bruce Anderson.

The graph above shows where a left-handed flower receives its pollen from. In total, 86.5% of the pollen received by left-handed flowers originated from right handed flowers. Surprisingly, one particular anther on right-handed flowers supplies most of this pollen (75.7%). A much smaller proportion of pollen comes from the same morph (14.2%), and of this, 8.1% comes from the same plant. Image: Bruce Anderson

Images of Wachendorfia paniculata: Wachendorfia paniculata in fynbos habitat, Table Mountain, Cape Town. Image: Andrew Massyn CC https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Wachendorfia+paniculata&title=Special:MediaSearch&type=image

: