Scientists from South Africa and Brazil have provided empirical evidence that pollen grains of rival plants may compete with one another for space on pollinators, thus influencing whose pollen is going to make it to the next flower – or not.

In an article published in The American Naturalist this week, they argue that because plants can manipulate where and how much pollen is placed on the bodies of pollinators, plants may have developed strategies that are similar to sperm manipulation in animals.

Some animals and insects have evolved complex structures on their penises which are thought to remove the sperm of rival males from the reproductive tracts of females before depositing their own. Unlike animals, however, plant mating does not involve direct contact between flowers. Consequently, manipulation of pollen (pollen carries plant sperm) needs to take place before the pollen reaches another flower - on the bodies of arriving pollinators.

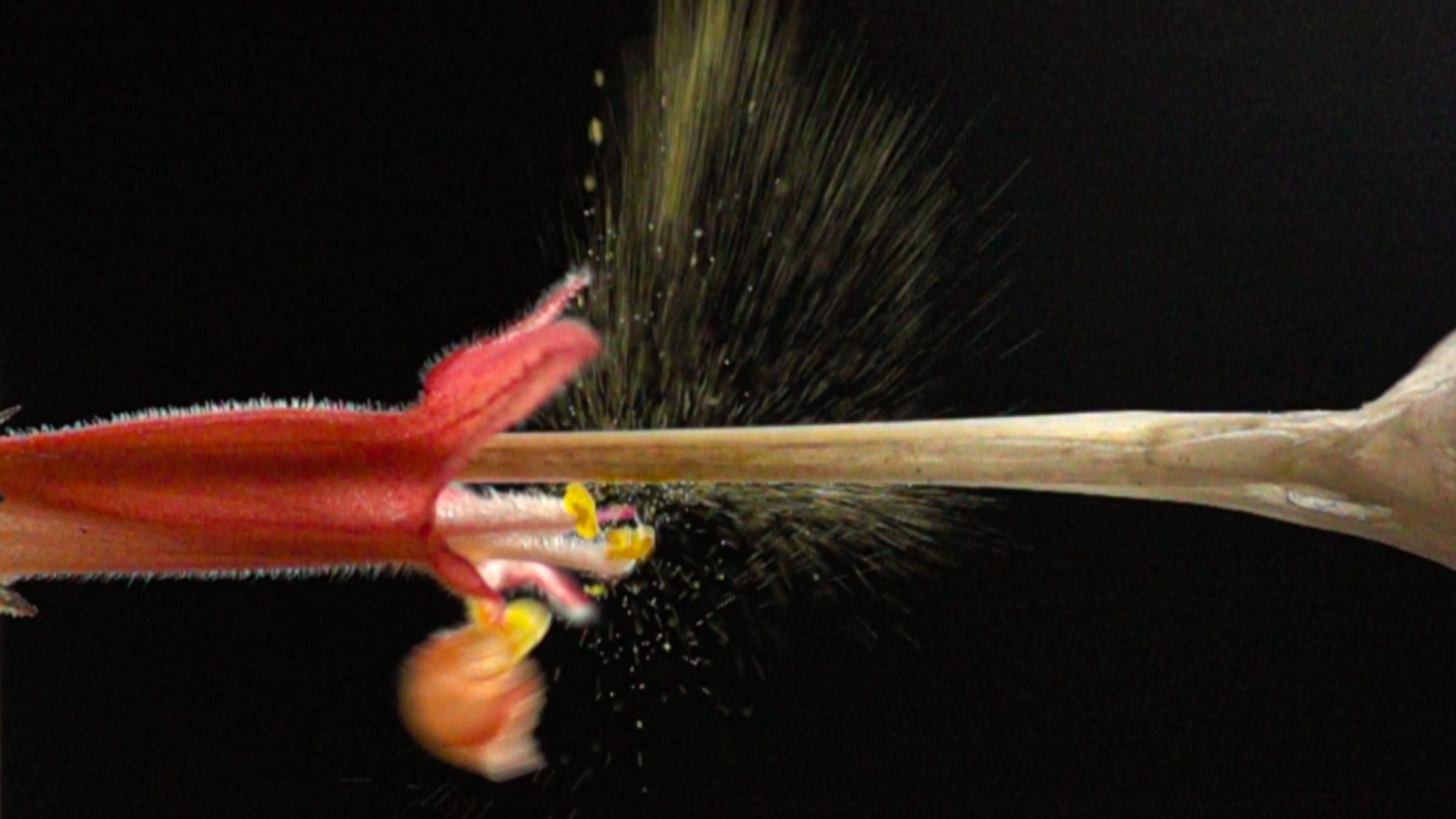

In the case of Hypenea macrantha, a deeply red flower endemic to Brazil, the researchers set up an experimental simulation, captured by slow motion video footage, showing how the flower employs a catapult-like mechanism to effectively remove pollen of rival flowers from the bill of a hummingbird skull, securely placing its own pollen on the same spot. Click here to view a slow motion video of this mechanism

This mechanism, called explosive pollen placement, is not unknown in the plant kingdom. However, this is the first time that researchers could provide empirical evidence of the efficacy of the mechanism by physically counting the number of quantum dot-labelled pollen removed by the explosion.

Prof. Bruce Anderson, an evolutionary ecologist in Stellenbosch University's Department of Botany and Zoology and first author on the article, says their findings provide evidence for the idea of competitive pollen removal in plants.

He explains: “Flowers visited by hummingbirds deposit their pollen on the hummingbird bills, but there is very little place for the pollen to be deposited. Flowers have evolved a catapult mechanism where pollen is shot at the bill of the hummingbird. The force of the ballistic grains dislodges previously deposited grains from rival plants allowing the flower to place its own grains onto a cleaner bill, thus increasing its chances of reproductive success."

In other words, a demonstration of effective pollen removal by floral explosion would provide the first evidence that male-male competition may have contributed to the evolution of this trait, they write in the article.

For Anderson, this finding shows that plants may be competing with one another in previously unimagined ways: “Until recently, no one has ever thought of looking for these kinds of structures in plants. For one thing, the flowers of one individual never interact directly with the flowers of another individual when mating occurs. This makes it hard for flowers to manipulate the male gametes of other flowers as animals can do," he explains.

But gamete manipulation may take place, not on other flowers, but on pollinators: “Imagine a pollinator arriving at a flower, covered in rival pollen from previously visited plants. The flower may find it difficult to place pollen on the pollinator because all of the space is taken up by the grains of rival plants and furthermore, even if the flower does manage to place pollen on the pollinator, its chances of reproductive success may be low as it has to compete with all the other rival pollen grains for access to the ovules of the next flower visited.

“So, what can a flower do? Like animals with penis adornments, it can evolve strategies to clean the rival grains from pollinators before placing their own grains," he comments.

Prof. Vinícius Brito, a botanist at the Federal University of Uberlândia in Brazil and co-author, says previously, floral explosion was thought to primarily aid in placing pollen grains on pollinators or even startle them into flying to new plants, thus dispersing pollen over greater distances.

“Our data suggest, however, that this mechanism may actually displace pollen from previous flowers, enhancing male reproductive success by increasing competition for space on the pollinators' bodies," he concludes.

Did you know?

- About 94% of plants are hermaphroditic – i.e. a plant's flowers have both male and female reproductive organs. To avoid self-pollination, individual flowers often go through a male phase and then a female phase.

- In the case of Hypenea macrantha, after the explosion is triggered, the anthers bent downwards, and the style elongates past the anthers as the flower enters its female phase.

- Slow motion video footage reveals that Hypenea macrantha's pollen travels at 2.62 metres per second after it is released (Usain Bolt runs approximately four times faster at 10.44 metres per second).

- The pollen catapult mechanism in white mulberries can exceed 170 metres per second, making it the fastest known movement in the plant and animal kingdom.

On the photo above, these frames capture the pollen explosion of a Hypenea macrantha flower when visited by a hummingbird. Images: Bruce Anderson and Vinicius Brito