Wednesday (1 December) is World Aids Day. In an opinion piece for Health24 (1 December), Prof Amy Slogrove from the Department of Paediatrics & Child Health writes that the time has come for children who are HIV-exposed and “HIV-free" to be fully incorporated in the global and South African HIV and child health agendas.

- Read the article below or click here for the piece as published.

Amy L. Slogrove*

Globally in 2020, there were about 36 million adults and 1.8 million children under 15 years of age living with HIV. In addition to this, there were 15.4 million children born to women with HIV who did not acquire HIV themselves, and are now surviving “HIV-free". This group of children are referred to as HIV-exposed and HIV-free.

On the one hand, this number of 15 million children HIV-exposed and HIV-free is a cause for celebration, especially on World Aids Day (1 December). It reflects how access to interventions to treat maternal HIV and prevent onward transmission of HIV to children have advanced magnificently over the last decade so that in many countries more than 95% of children born to women with HIV will remain HIV-free. On the other hand, this number is a cause for pause. It represents the persistently high HIV prevalence amongst adolescent girls and women in sub-Saharan Africa and thus exposure by their unborn children to HIV and antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) during pregnancy.

In southern African countries, including Eswatini, Lesotho and South Africa, an astounding 25%, or one in every four, children are HIV-exposed (born to women with HIV) and HIV-free. And furthermore, one in every four children in the world who are HIV-exposed and HIV-free are in South Africa. Yet, there has been little public discussion globally or in South Africa about the package of potential risks experienced by children born to women with HIV, even when these children avoid HIV acquisition and remain “HIV-free".

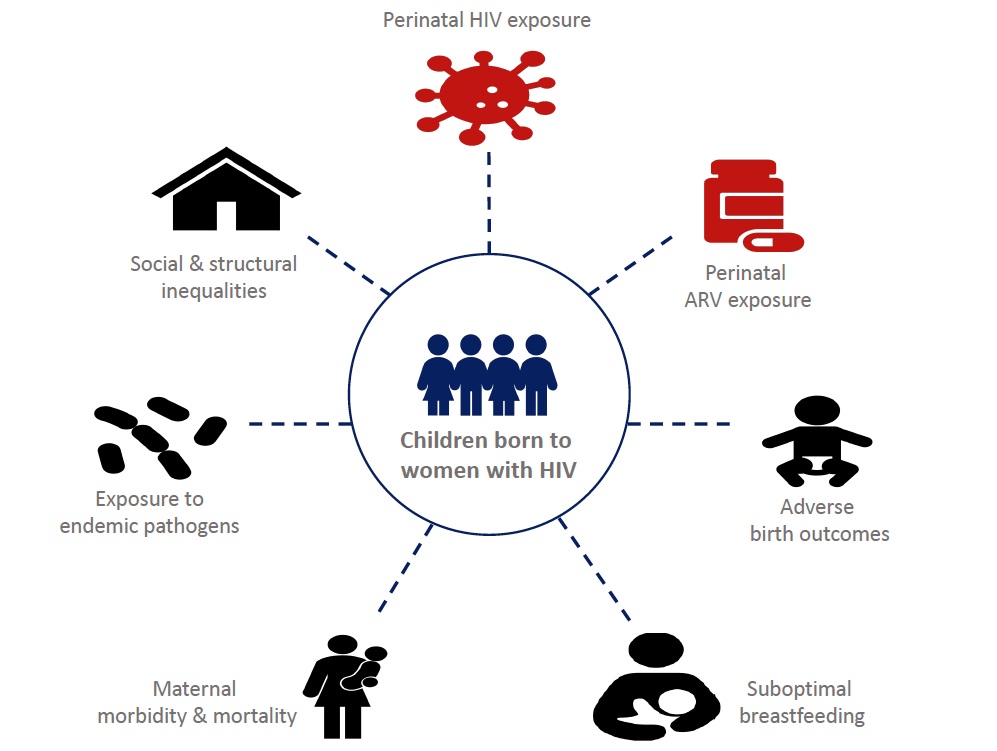

These risks include unique exposures to HIV and ARVs during pregnancy and sometimes also in the first few months of life. They also include risks that can negatively impact child outcomes in any child irrespective of HIV exposure (universal exposures) but that occur more often in children born to women with HIV. These include being born too small (growth restricted) or too soon (preterm), not receiving the full benefits of breastfeeding, having mothers who are unwell or who may have died during their childhood, greater exposure to other infectious diseases in the household such as tuberculosis, and social and structural inequalities experienced by families affected by HIV including stigma, social exclusion, poverty and other adversities as the Figure below shows. This package of possible exposures is resulting in health and developmental inequalities among children born to women with HIV even without HIV in their children.

Early in the HIV epidemic, before antiretroviral therapy (ART) was widely available, it was accepted that there were inevitable consequences of HIV to the health of pregnant women and their unborn children. A womb altered by a severe viral infection cannot provide the environment required for a fetus to optimally grow and develop. This was seen early in the HIV pandemic by increased rates of stillbirth, fetal growth restriction and preterm birth. This was followed as children grew up, even without HIV, by more sickness from common childhood infections such as pneumonia and diarrhoe and higher infant and child mortality compared to children born to women without HIV. It was thought that factors like poor maternal health, inability to safely breastfeed, and poverty were the most likely drivers of these outcomes. However, little was done to study and fully understand this.

As ART became globally accessible, it was then assumed by providers and policymakers of national and global HIV programmes that with improved maternal health and well-being, and the opportunity for safer breastfeeding in women on ART, pregnancy and child health outcomes would also improve. However, recent evidence indicates that this is not necessarily the case. Children born to women with HIV on ART are still being born too small and too soon twice as often as children born to women without HIV. They also require hospitalization 2 to 3 times more often in early childhood, most frequently due to common childhood infectious diseases that present more severely. And some are falling behind on expected growth and early neurodevelopmental milestones, particularly in speech and language development. This can herald lifelong learning disabilities with poorer school completion as they age that is linked to suboptimal income-generating potential during adulthood as a result.

With universal ART, the goal for adults living with HIV is one of equivalence in quality of life and life expectancy compared to adults living without HIV, and this goal should be no different for the children born to women with HIV. We must look beyond only preventing HIV infection but also ensure optimal early childhood health and development for all children born to women with HIV. Foundational to achieving this goal is to engage more directly in conversations with mothers and families in joint-learning around how to optimize outcomes for all their children. Mothers with HIV have voiced their distress at seeing but not understanding the relative developmental differences in their children compared to their peers, recognizing that being HIV-free is not always enough for their children. Simultaneously, mothers are concerned about preserving confidentiality for their families and the dilemma of avoiding stigma-by-association and securing the innocence of childhood unburdened by the complication of HIV.

It is time for children who are HIV-exposed and HIV-free to be fully incorporated in the global and South African HIV and child health agendas. This means inclusion in goals and targets for the HIV pandemic that can be monitored through strengthened country-level collection of child outcome indicators disaggregated by HIV exposure and not only HIV infection status.

Research investments have started, but more are needed to fund partnerships in high HIV prevalence settings, like South Africa, that are designed specifically to understand the mechanisms and potential interventions to optimize the trajectory of these children. It is the responsibility now of clinicians, researchers, and policymakers to transparently and accurately share with families affected by HIV what is known, what remains unknown, and what is being done to better understand the benefits, risks, and consequences of in utero and early-life exposure to ARVs, HIV and an HIV-affected environment.

Figure: The package of risks for suboptimal early childhood health and development in children who are HIV-exposed and HIV-free. The red-colored icons indicate risk factors unique to children HIV-exposed and HIV-free, while black-colored icons indicate universal risk factors.

*Amy L. Slogrove is an Associate Professor in the Department of Paediatrics & Child Health in the Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences at Stellenbosch University. This piece is based on her recent article in the Journal of the International AIDS Society (November 2021).