Bacteria may be responsible for more than we suspect. Especially when it comes to inflammatory diseases such as Type 2 diabetes.

Prof. Resia Pretorius from Stellenbosch University (SU) in South Africa and Prof. Douglas B. Kell from The University of Manchester in the United Kingdom have conducted a series of studies that are drastically changing the way scientists think about the effect bacteria have on a number of diseases including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Sepsis, Rheumatoid Arthritis, and most recently Type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Previously, Pretorius and Kell have established that these chronic inflammatory diseases also have a microbial origin. “If the bacteria were active, or replicating, as in the case of infectious diseases, we would have known all about that," says Kell. “But the microbes are not replicating, they're mainly actually dormant."

Because their dormant nature meant that they did not manifest under standard microbial test conditions, bacteria were previously thought to be absent from human blood, consistent with the view that blood is 'sterile'. However, high levels of iron in blood (typical of inflammatory diseases) can effectively bring these bacteria back to life. Previous research suggested that under these conditions, the bacteria start replicating and secreting lipopolysaccharides (LPS), leading to increased inflammation.

Cellphone users use this link.

The one thing these chronic diseases have in common is constantly elevated levels of inflammation. Pretorius and Kell had already established that anomalous amyloidogenic blood clotting, a cause of inflammation, is linked to and can be experimentally induced by bacterial cell wall constituents such as LPS and Lipoteichoic acid (LTA). These are cell wall components of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, respectively. Read more at previous research article on this topic.

These coagulopathies (adverse blood clotting) are also typical of inflammatory diseases and the researchers have long shown that they lead to amyloid formation, where the blood clotting proteins (called fibrinogen) are structurally deformed from a-helixes to a flat b-sheet-like structures, potentially leading to cell death and neuro-degeneration.

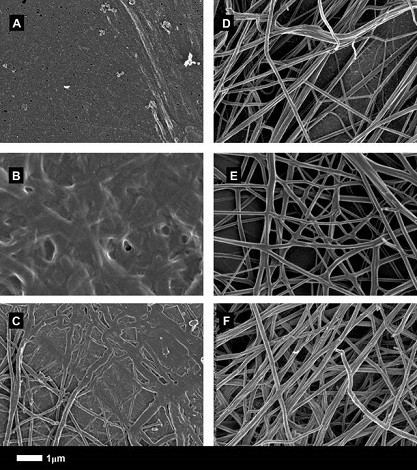

As a result, the fibrin fibres of blood clots in diseased individuals are distinctly different from those of healthy individuals. This can be visualised microscopically and is discussed in various publications from the group. “In normal blood clots, these fibres would look like a bowl of spaghetti" explains Pretorius. “But in diseased individuals, their blood clots look matted with large fused and condensed fibres. They can also be observed with special stains that fluoresce in the presence of amyloid."

The researchers found that this changed clot structure is present in all inflammatory conditions studied, now including Type 2 diabetes. But what is the link between this abnormal clot formation, bacteria, LPS and TLA? And are there any molecules that may “mop up" LPS or LTA and that might be circulating in the blood of people with inflammatory diseases?

In their 2017 study, recently published in Scientific Reports (a Nature publication), Pretorius and Kell, along with MSc student Ms Sthembile Mbotwe from the University of Pretoria, investigated the effect of LPS-binding protein (LBP), which is normally produced by all individuals. They added LBP to blood from T2D patients (and also to healthy blood after the addition of LPS). Previously they had showed that LPS causes abnormal clot formation when added to healthy blood, and that this could be reversed by LBP. In this publication they showed that LBP could also reverse the adverse clot structure in T2D blood. This process was confirmed by both scanning electron microscopy and super-resolution confocal microscopy. The conclusion is clear: bacterial LPS is a significant player in the development and maintenance of T2D and its disabling sequelae.

“In an inflamed situation, large amounts of LPS probably prevent LBP from doing its work properly," explains Pretorius.

So what does this mean in terms of treatment?

“We now have a considerable amount of evidence, much of it new, that in contrast to the current strategies for attacking T2D, the recognition that it involves dormant microbes, chronic inflammatory processes and coagulopathies, offer new opportunities for treatment," the researchers conclude.

About the researchers

Prof. Resia Pretorius is a full professor in the Department of Physiological Sciences at Stellenbosch University. Her main research objective and major scientific achievement has been to create a vital mind-shift in the understanding of inflammation by developing new approaches to study the role of coagulation parameters in inflammatory diseases. She has developed rapid diagnostic methods for these purposes, with innovative ultrastructure and viscoelastic techniques that include confocal microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), and thromboelastography (TEG).

Prof. Douglas Kell is a professor at the School of Chemistry and The Manchester Institute of Biotechnology at the University of Manchester, United Kingdom. He specializes in systems biology, where he tries to understand complex biological systems.

On the photo above, imaged here are micrographs of Type 2 diabetes clots before and after treatment with LPS-binding protein. When visualised microscopically, the fibrin fibres of the blood clots in diseased individuals (image A, B and C) are distinctly different after treatment (images D, E and F). In normal blood clots, the fibres look like a bowl of spaghetti, but in diseased individuals, their blood clots look matted with large fused and condensed fibres. Micrographs were taken with a Scanning Electron Microscope. Images: Dr Resia Pretorius

Media enquiries

Prof. Resia Pretorius

Tel: +27 21 808 3143

E-mail: resiap@sun.ac.za

Prof. Douglas Kell

E-mail: dbk@manchester.ac.uk

Media release issued by

Wiida Fourie-Basson, Media: Faculty of Science, Stellenbosch University

E-mail science@sun.ac.za

Tel +27 21 808 2684

www.sun.ac.za/science

Jordan Kenny, News and Media Relations Officer, Faculty of Science and Engineering, Manchester University

Tel +44 (0)161 275 8257

Mob +44 (0)7748 747079

E-mail jordan.kenny@manchester.ac.uk